The Last Descendants Installation and Video Project

THE LAST DESCENDANTS

Artist Statement:

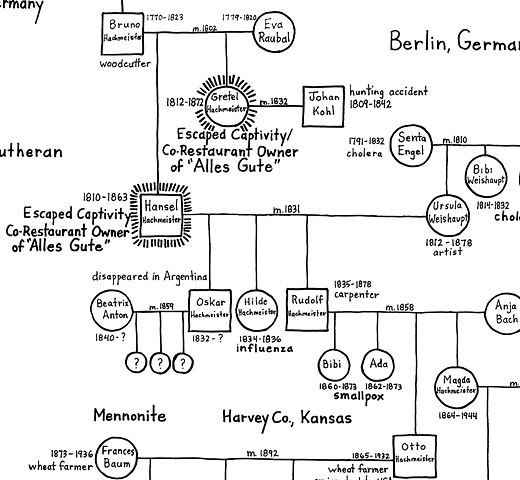

What we know as history is often the result of memory, imagination and omission. Families hold back facts to protect the images of loved one. Historians work with what is known at the time, often with only pieces of the truth. Memory, both voluntary and involuntary, is patched together with fragments that may change over time. In The Last Descendants, I tell the imagined family histories of well-known fictional characters – The Lone Ranger, Huckleberry Finn and Hansel and Gretel through scripted interviews, family trees, and invented family heirlooms to create a suspension of disbelief. I use a hybrid of fact and fiction to show that what we think we know about people and events, real or otherwise, personal friends or public figures, may not be the truth.

When I was in the seventh grade, I wrote a glowing report on all the good that President Andrew Jackson did for the Indians. It was only later, that I learned, on my own, that he was he was responsible for Indian removal, ethnic cleansing and The Trail of Tears. Around the same time that I wrote the Jackson report, I was reading a lot of fiction that didn’t hold back a thing. Books like Strange Fruit, by Lillian Smith, that I’d found hidden in my father’s tool shed. Smith’s book, published in 1944, is a story about racial strife in a small, Southern town. It, along with Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, Roth’s Call It Sleep, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and Agee’s A Death in the Family, began to articulate for me what I knew intuitively and experientially, that events have considerable context and that people have complicated feelings and motives for both their actions and inactions. I began to realize, as author David McCollough wrote, “History is who we are and why we are the way we are.”

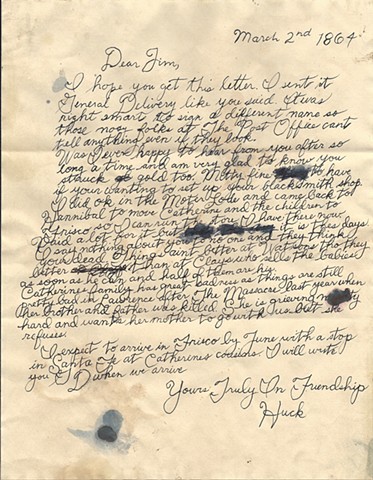

Fiction informed my understanding of history, and through the study of history, I expanded the choices of novels I read. In this body of work, I mix fantasy with fact to create pictures of both individual and public histories that allow me to engage with a wide-range of issues, such as war, persecution, immigration, ethnicity, epidemics, identity and religion. I also explore love, loss and the power of the human spirit. Invention and fact weave narratives in the video interviews and family trees. When I refer to a particular battle or suggest a political event, I get the dates right. However, I use the freedom I gain from invention to include humor and irony in the storytelling. Historian Allen Nevins wrote, “(History) is a painting; and, like all works of art, it fails of the highest truth unless imagination and ideas are mixed with the paints.”

REVIEW IN THE KANSAS CITY STAR

CLIMBING A FICTIONAL FAMILY TREE

Artist Judith Levy’'s 'documentaries' delve into the genealogies of some well-known names.

By DANA SELF

THE KANSAS CITY STAR

The personal is always political, and history is not a series of fixed moments in time, but rather perspectives and truths that shift depending on who tells the story.

Lawrence-based artist Judith Levy excavates the past and reconstructs it through her fictional historical documentaries. She stitches together social, political and economic realities of the times in which fictional characters lived and how those histories shape us.

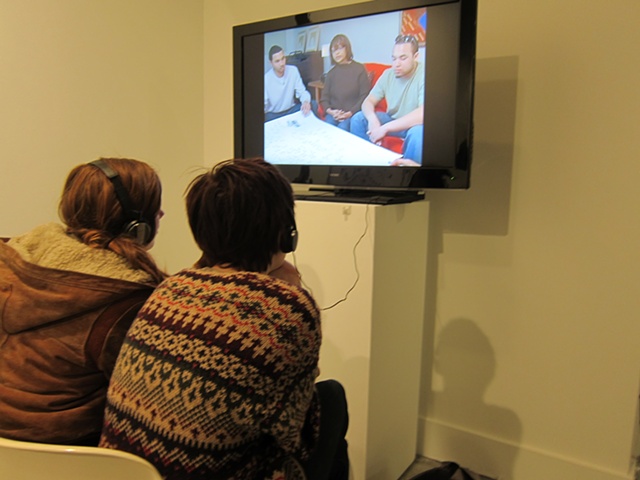

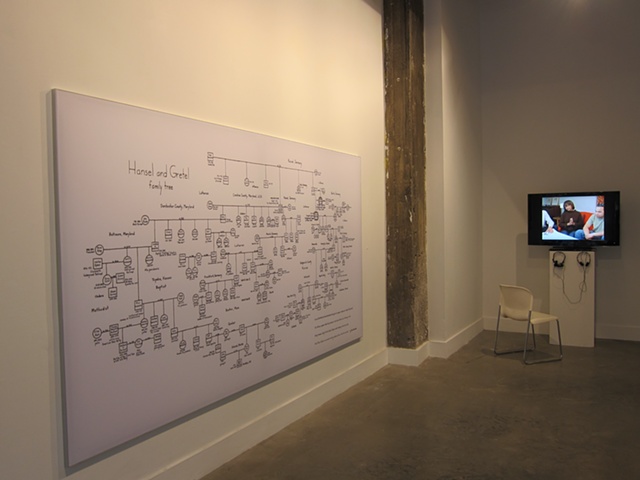

In her faux documentary film series "The Last Descendants, " Levy interviews the imaginary last relatives of the Lone Ranger, Huckleberry Finn, and Hansel and Gretel.

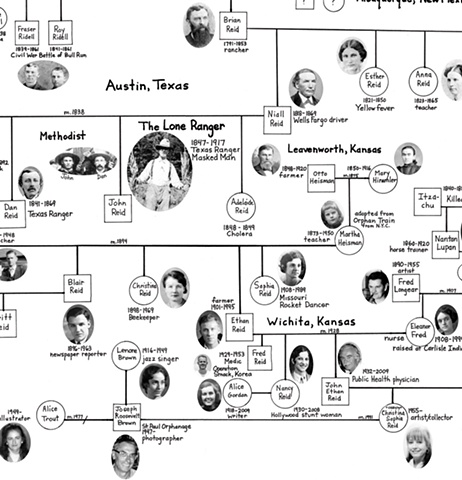

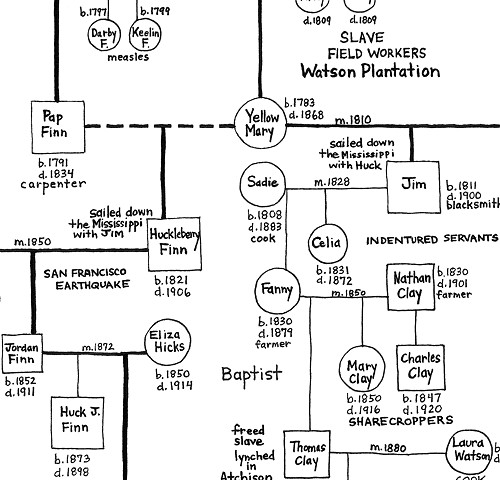

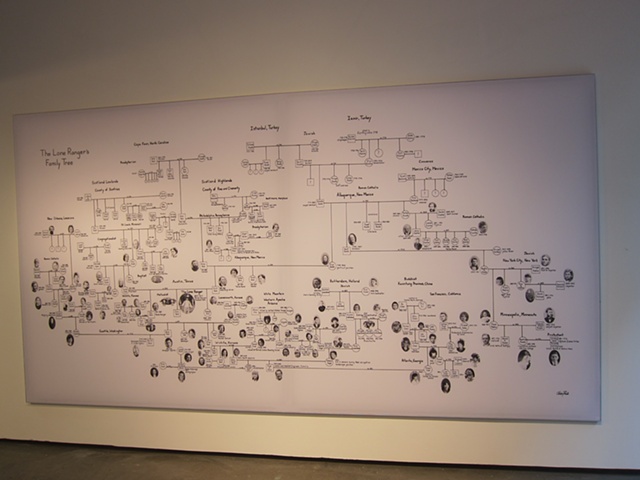

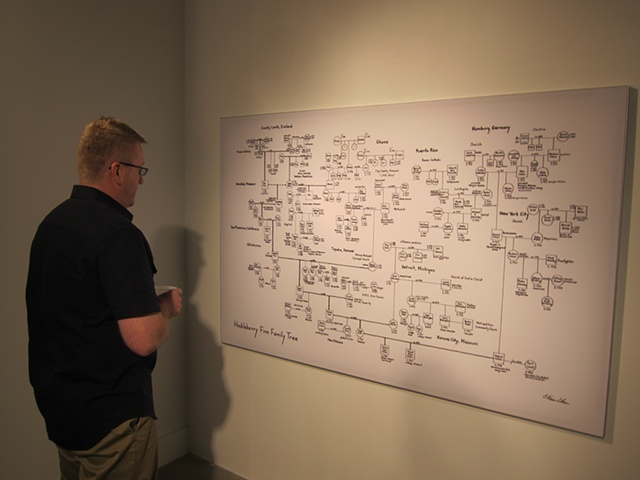

Levy constructs elaborate family trees that map immigration patterns, slavery, and American social, cultural and racial developments. These family trees, which are central to the exhibition, help establish her characters' invented lives.

Huck Finn's ersatz familial history reveals that his mother was black, his traveling companion Jim was his half brother, and Huck himself was the product of rape. This family tree cleaves wide open the painful realities of American slavery and its potent aftermath.

Levy interviews Faye Finn-Cohen and her two sons in "Huckleberry Finn." Among issues of paternity and racism, they discuss not getting invited to the "white" side of the Finn family reunions. They ruefully ponder how the "black side of the Finn family really wanted to do it, " but the white side did not. "I really want that Finn Family Fun T-shirt, " quips one of the sons, ironically.

The interview telegraphs an uncomfortable reality about a fictional family that mirrors concrete issues.

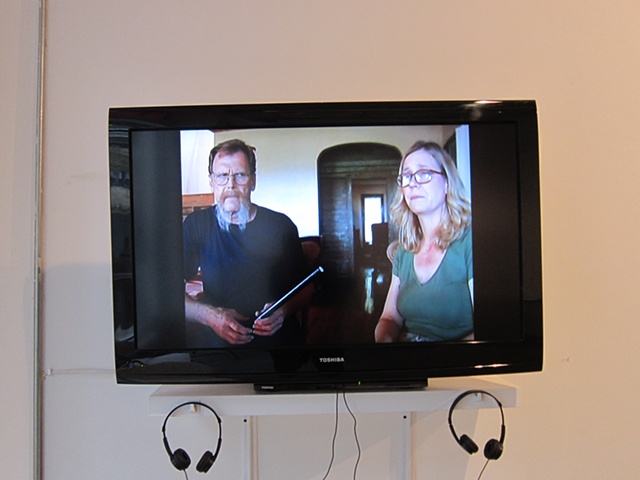

In "Hansel & Gretel, " the last descendants are siblings portrayed by sculptor John Hachmeister and his wife, Diane. As if they were siblings, they fractiously interrupt each other and quibble throughout the interview about whether Hansel or Gretel saved the pair from their forest misadventure, who in the family tree might have been a Nazi collaborator and other familial secrets.

Toward the end Levy raises a question about jewels the Grimm brothers were said to have paid Hansel and Gretel's father for "exclusive rights" to their story. Levy cleverly folds contemporary journalistic sensationalism into the story.

In "The Lone Ranger, " Levy speculates about the Lone Ranger's sexuality and his relationship with Tonto. That she makes the Lone Ranger a descendant of Turkish Sephardic Jews allows Levy to "challenge conventional notions of heroes, " according to her email exchange.

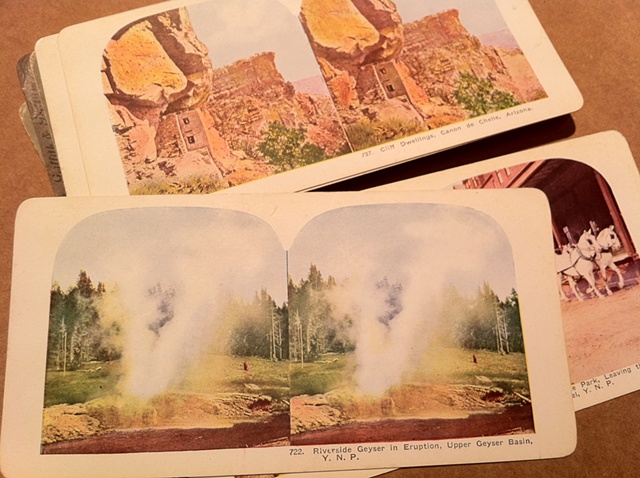

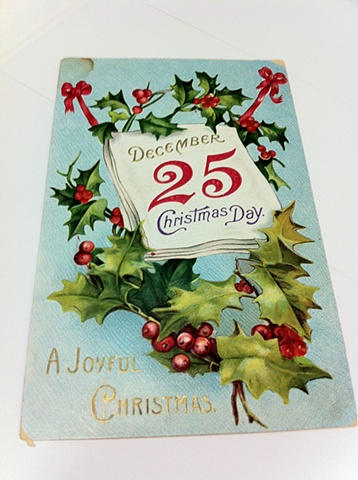

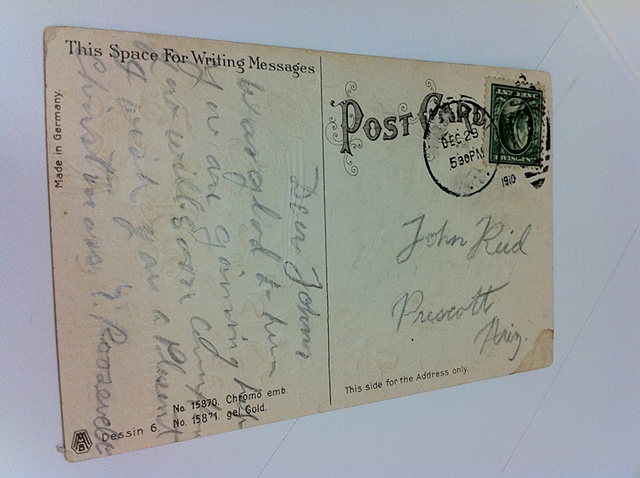

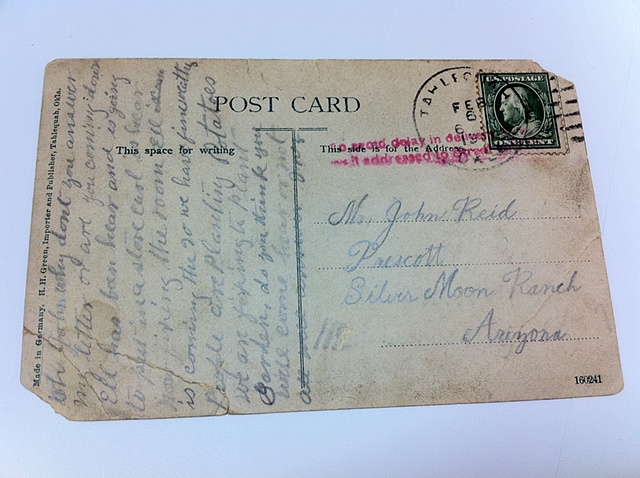

An assortment of bogus Lone Ranger family heirlooms rounds out the exhibition. Displayed in a glass case, period pocket watches, spectacles, a ring that was a "gift from Tonto" and other mementos make up the collection.

Viewing these carefully labeled items, it's easy to forget that it's all an elaborate and skillfully deployed invention.

By paradoxically fictionalizing characters to unpack and examine history, Levy expands a dialogue about how we understand history's various truths and how they all may be interpreted differently and discontinuously over time.

"The Last Descendants" is a complex, multilayered, narrative exhibition exquisitely crafted and acted by Levy.

The Last Descendants

an essay by

Kris Imants Ercums

Curator of Global Contempoary and Asian Art

Spencer Museum of Art

In her recent series The Last Descendants Judith Levy charts the rich complexity of an individual through meticulously drawn “family trees” that outline in startling detail the lineage of noted fictional personalities: Huck Finn; Hansel and Gretel; and most recently, the Lone Ranger. Each document is paired with a dramatized video interview with the “living descendants” of these mythic characters. The use of documentary evidence intentionally staged as “proof” for family heritage is part of an overall strategy by Levy to re-imagine history. Deploying a wide range of research methods from rummaging through junk stores for just-the-right photo to reading broadly on the major issues that have shaped society like war and disease, Levy blurs the distinction between the grand narrative of historical fact and a fictionalized, highly personal imagining of the individual. In this way Levy takes advantage of Voltaire’s observation that history “consists of a series of accumulated imaginative inventions.”

Through this work Levy confronts major issues like migration, race and sexuality that are at the heart of contemporary American identity. By recasting cultural memory through the personal lineage of iconic, albeit entirely fictional characters, Levy preys on our naïveté of American popular culture—“Huck Finn was Jewish?” By suspending belief, Levy is able probe issues important to her. This broad lens brings into focus the monumental complexity of human interaction that goes into the construction of each personal narrative. It also distorts broader perceptions of reality and imagination. Tackling romantic notions like “America the Melting Pot,” these poignant investigations bring to the foreground monumental forces like religion, ethnic background and sexual desire that shape identity.

However, mythology often warns us against looking back—think of Lot’s wife turned to salt. And great writers like Marcel Proust recall how disappointing memory can be, as it never truly restores the past. Scientists who work on memory, also call into question the pure form of remembering that we often times idealize. Rather, current research suggests that we only recall our past in a fragmented, discontinuous way. Memory is not archived as a whole, but exists as a highly selective and constantly changing phenomenon. This subjectivity, the imaginative potential embedded in memory, is at the core of Levy’s The Last Descendants. While seemingly whole and complete, each “fact” is a carefully poised fragment, a carefully constructed “lie” that challenges “truth” as something ultimately subjective and constructed. Thus, the series is far from a Proustian attempt to grasp at the past—that fleeting and unattainable taste of a Madeleine cookie—but instead the work is an elegiac journey through the workings of individual imagination.

Kris Imants Ercums

Curator of Global Contempoary and Asian Art

Spencer Museum of Art